Globalisation isn’t dead, it needs a reset

Beset by war, upended by broken supply chains, ravaged by a deadly pandemic and exacerbated by rapid inflation–the globalising forces that have long shaped our world threaten to come undone.

Some politicians, economists and experts have pronounced globalisation dead. Many more suggest we’re witnessing a rapid decline. Day by day, the chorus of naysayers grows louder, while de-globalisation rhetoric shapes the global media narrative as the world lurches from one crisis to the next.

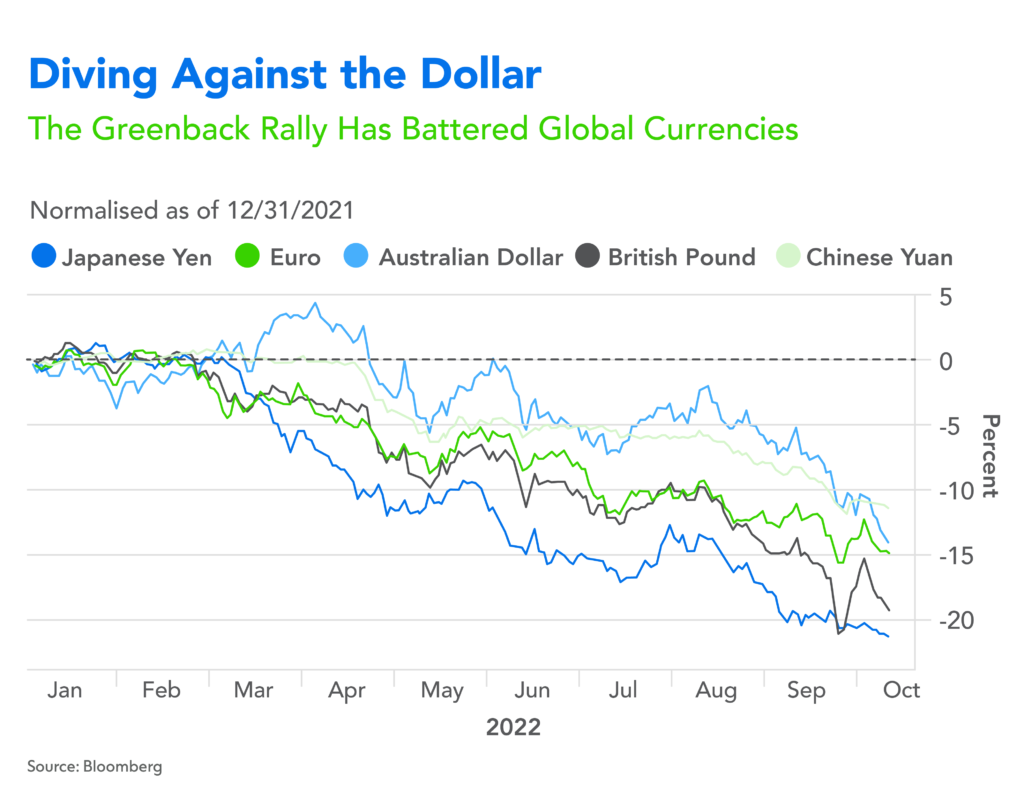

For some, globalisation’s demise would not be unwelcome. It has been blamed for uneven economic development, cultural homogenisation, environmental degradation, the exploitation of foreign workers and much more. A wave of nationalist movements echoes growing discontent with the prevailing multilateral system. Meanwhile, recent US Dollar strength underscores the perils of economic integration, with the greenback’s rally pushing currencies across the world into a spiral of doom against a backdrop of inflation.

“The Federal Reserve’s actions on interest rates and resulting dollar strength have created challenges in terms of capital outflows in several emerging markets,” José Viñals, Group Chairman of Standard Chartered said at a recent breakfast session on resetting globalisation in an era of uncertainty, hosted by Standard Chartered at the 2022 Annual Meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group in Washington, D.C. “This has made life more difficult in low-income countries with high levels of external debt.”

Yet, globalisation has its champions, and for good reason. It has increased the global flow of capital, yielded better products at lower prices, advanced technology and innovation and improved international collaboration. Globalisation also bettered billions of lives; in the period of rapid globalisation from 1988 to 2013, the global poverty headcount ratio declined from 35% to 10.7%.

“Globalisation has been blamed for the rapid spread of Covid, but also for the comparatively quick resolution with the development and deployment of vaccines,” Viñals noted. “It is lionised for lifting millions out of poverty but also for the uneven distribution of gains that have trapped individuals and countries in a downward cycle. Surely, there are gradations, and globalisation cannot be described so simply and in such stark dichotomies. Recalibrating globalisation to make it more just, equitable and sustainable is surely called for. But is the best approach to reform or replace that system?”

First and foremost, we must acknowledge that many of the relationships built over the past several decades are too deep to unwind and the benefits too great to relinquish. Trade, data and capital flows suggest globalisation is here to stay.

“International trade was really the key to success of so many civilisations,” Jeremy Siegel, Russell E. Palmer Professor Emeritus of Finance at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania said during the breakfast, in conversation with Viñals. “Looking back at the past century, the ability to manufacture at scale, transfer technology and to create infrastructure that could produce all these goods elsewhere was a major shift both economically and socially. The question today is how do we keep the gains that economic specialisation and globalisation bring?”

Global trade reached a record $28.5 trillion in 2021, increasing 13% relative to pre-pandemic levels of 2019. While a confluence of waning economic growth, inflation and changing monetary policy has the World Trade Organisation (WTO), IMF and OECD forecasting a deceleration in trade growth ahead, global supply chains and trade corridors are more integrated than ever. Trade among APAC economies, for instance, reached its highest level in three decades last year. And the WTO recently recorded a record number of Regional Trade Agreements (RTA) in force as well as new RTA notifications.

Consumers play a huge role. In 2020, the world recorded 9.3 billion cross-border e-commerce orders. Around 60% were intercontinental. Conservative estimates suggest cross-border e-commerce will reach $1 trillion in merchandise value by 2030 from around $300 billion in 2020 as consumer habits and preferences evolve.

Growing digital connectivity underpins that trend. An additional 782 million people came online globally in the first two years of the Covid pandemic. Digitalisation continues to change society, the economy and the ways in which people interact. As digital interactions become increasingly central to our lives, monthly global data traffic is forecast to more than triple from 230 exabytes in 2020 to 780 exabytes by 2026.

“The globalisation of culture, of information and of political ideas is happening much faster and in a different way than it had ever happened before,” Anne Applebaum, New York Times bestselling author, journalist and international affairs expert said at the breakfast. “ We now have a globalised internet, in which there’s essentially a single conversation. And that means that every country needs to think about how it plays and how it’s understood, not only at home, but also abroad.”

Capital continues to flow across borders, too. In 2021, global foreign direct investment flows reached $1.58 trillion, driven by mergers and acquisitions as well as rapid growth in international project finance. Economic headwinds upended momentum for much of 2022, yet the long-term trend of money pursuing opportunity across borders remains intact and will for the foreseeable future.

While the flow of goods, data and capital indicate the connections that have long defined our world are here to stay, we must recalibrate them to ensure equitable and sustainable growth throughout the 21st century.

“Trade has changed fundamentally from the exchange of goods and services to include data, ideas and capital, facilitated by new digital platforms and emerging technologies,” Viñals said. “We now need a global trade system that accounts for these shifts and addresses current issues, to become more accessible and sustainable.”

Integrating less developed markets and small businesses into global trade will prove vital. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) account for roughly 90% of businesses and more than half of employment worldwide. They also contribute up to 40% of GDP in emerging economies. Globalisation needs to give SMEs the opportunity to participate in global supply chains.

Technology can lift participation in global trade, yielding benefits across productivity, agility, visibility, resilience and more. Yet, the pandemic highlighted challenges that SMEs face with tech adoption. Only 23% globally were able to dedicate resources to new digital tools, with most citing inadequate financing and skills as key barriers.

Sustainability must also remain front of mind as the world strives to achieve net-zero targets by the middle of this century. That means addressing longstanding concerns around everything from transport emissions and commodity-driven deforestation to supply-chain-linked environmental destruction. Success entails the development of global governance standards and regulatory coherence for sustainability. Private sector initiatives such as Standard Chartered’s Sustainable Trade Finance Proposition, which is designed to help companies implement more sustainable practices across their ecosystems and supply chains, will also play a crucial role.

Interoperability between the various digital trade ecosystems also demands our attention as it is a requisite for the scale up of digital trade flows–for example, those involving transfer of title and negotiable instruments such as bills of lading. To achieve equitable growth, we must develop future-fit policies and frameworks that ensure interoperability across markets, platforms and businesses at different stages of advancement, linking physical and financial supply chains and helping innovations achieve wider adoption.

“We need to understand that globalisation has been really a force for good,” Viñals added. “It has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, it has contributed to tremendous integration of many markets in the global economy. But again, there are many edges that need to be polished. One of the things that Standard Chartered stands for is resetting globalisation to make it fairer, more inclusive and more sustainable.”