Uncomfortably optimistic: why China and Asia can support global growth

The global economy is set to grow at 3.9 per cent in 2018, the fastest pace in five years. As the news cycle keeps reminding us, there are considerable risks to this outlook, in particular the consequences of the end of the era of quantitative easing and the threat of a full-scale US-China trade war. Nonetheless, there are reasons to remain ‘uncomfortably optimistic’ about growth in 2018 and 2019, not least because of the leading role played by Asia-Pacific economies.

Using purchasing-power parity (PPP) exchange rates, Asia ex-Japan will contribute nearly 60 per cent of global growth this year; China alone will contribute 31 per cent. Not only is this a huge change from a decade ago, but it is likely to remain the case for the next decade or two as well. Assuming the very worst tail risks do not transpire – which is not our forecast, nor currently expected by global markets – Asia-Pacific economies are well placed to continue driving growth in the short term and beyond.

Firstly, China has the means to counter the effects of the trade sanctions imposed by the US. To be sure, the economic impact is proportional to the severity of the measures taken: in the worst-case scenario (the US bans all imports from China) losses could rise to 3.2 per cent of its GDP. However, factoring in the measures taken and approved so far, we still expect China’s economy will grow 6.6 per cent this year, only a modest slowdown from 6.9 per cent in 2017.

This is partly because China has already adjusted its policies to support domestic demand. According to our calculation, if the 2018 budget is fully implemented, the fiscal deficit will be 0.9 per cent of GDP (or RMB1.1 trillion) higher than last year. We see this policy shift as a clear signal that the government is committed to achieving its 6.5 per cent growth target for 2018.

It’s true that China also faces domestic challenges – a housing market downtrend and deleveraging, for instance – but policymakers have skilfully managed the twin goals of stabilising corporate debt and delivering economic growth. This has been accompanied by a subtle change in policy from pure deleveraging to stabilising leverage, a shift from just 12 months ago to support demand. Remarkably, China needs only to achieve growth of 6.3 per cent annually between now and 2020 to reach its target of doubling 2010 real GDP by 2020, something we think can be relatively easily achieved.

Another point in China’s favour is that the impact of the end of quantitative easing, which has put a range of emerging markets under pressure, is not an issue given its lack of external exposure of the kind that has hit Turkey, Argentina and others (i.e. severe current account and fiscal deficits, and large short-term foreign-currency external debt).

Though China may in fact see an annual current account deficit next year, owing to the strength of domestic demand, it faces a wave of inbound foreign investment rather than an exodus. As it continues to remove technical barriers to investing in its capital markets, and as mainland assets are included on benchmark indices as a result, global investors will be obliged to buy to adjust their underweight positions. No one expects RMB depreciation to be a one-way bet.

Exchange rate flexibility is already playing a role in limiting the global economic impact of a trade war on other major economies, too. Considering that a 10 per cent increase in what US consumers would have to pay for imports from China would not be too different from the impact of a similar move in exchange rates (which in any event has been countered by USD/RMB moves this year), worries about the impact may have been overdone.

It is also a fact that identifying which countries would win, and which would lose, from the fallout is far from easy given the immensely complex supply chains and economic inter-relationships that now underpin global trade.

For instance, the dependence of the US economy on demand from China, by our estimates, is increasing (accounting for around 1 per cent of its GDP, triple the level of a decade ago) while China’s exposure to US demand is falling (accounting for around 3 per cent of GDP, half what it was ten years ago). Other research has shown that 1 in 5 jobs in the US is related to international trade, up from 1 in 10 25 years ago. A protracted trade war would therefore hurt the US proportionately more the longer it went on (though it’s important to remember that politics, rather than rational economic decision-making, is likely to continue to drive US policy on this front).

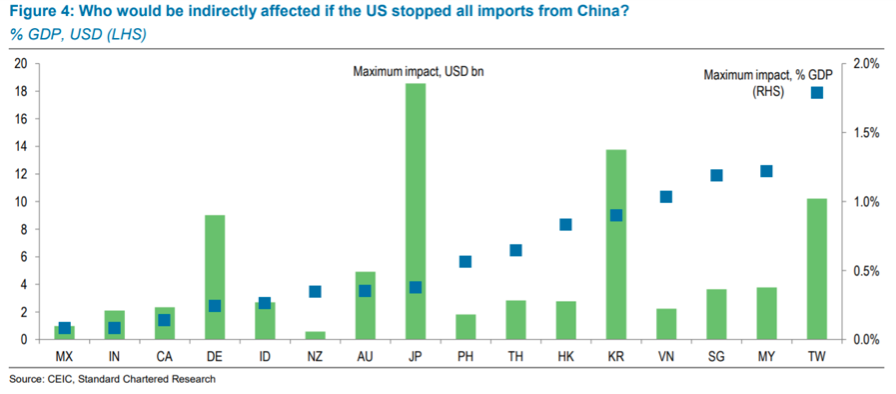

These new trade and demand inter-relationships are crucial in Asia-Pacific economies. Our research also finds that a trade war would have a wide impact on China’s supply chain partners in the region: in an extreme scenario where the US halts all China imports, Malaysia’s GDP, for instance, might be affected by 1.2 percentage points.

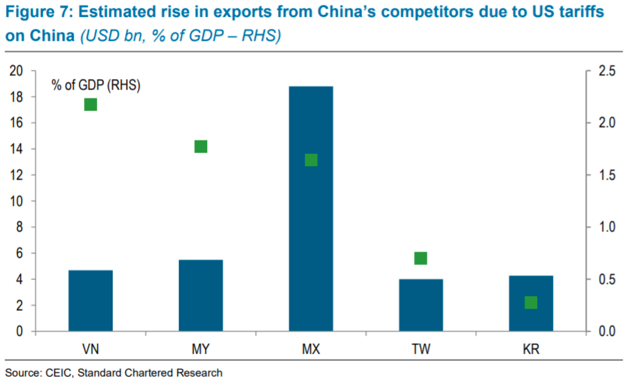

However, four of the top five ‘losers’ – Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan and South Korea – are also likely to be among the economies that would gain most from export trade diversion due to targeted US tariffs on China. Vietnam, for instance, could see exports diverted from China increasing by 2.2 per cent of GDP.

Another consequence is that these economies could see some diverted investment, as companies seek to reduce their exposure to China and diversify their production around the region. ASEAN nations (as well as Mexico) are particularly well positioned for this, assuming they could shift to selling directly to the US rather than participating in the supply chain to the US via China. Rising wages in China means this is already happening.

Then there is the fact that demand within the region is likely to keep growing: ASEAN-China is the trade corridor with the most exciting growth potential, part of the reason we expect to see the region powering global GDP growth for years to come.

China’s attempts to promote global trade networks, and open links between Asia and the rest of the world via the Belt and Road initiative underlines this expectation. It also serves as a counterpoint to the protectionism that has been rising since the global financial crisis, demonstrated most dramatically by President Trump’s anti-globalisation, America-first agenda.

Criticisms of China’s push for globalisation have risen in parallel with the growing scale and importance of China’s economy. However, China remains far from dominating the agenda, in part due to the lack of a multilateral platforms to drive its ambitions: the likes of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) or Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have yet to match their well-established counterparts in the IMF, World Bank or WTO. The Belt and Road has also been facing its own challenges that require China to become more transparent by better aligning itself with prevailing international standards in areas such as cross-border debt and procurement policies.

Regardless, we see a stronger and more immediate impact from China by being a more positive force in stimulating international cooperation and trade via the Belt and Road.

Of course, the risks to this outlook cannot be ignored. While the global economy is likely to show its resilience in 2018 and 2019, how a protracted trade war will affect sentiment and investment plans remains to be seen. Longer term, growth will slow: if China reaches its 2020 GDP target, the policy focus on growth will be eased, while the impact of the US fiscal stimulus will be waning. The demographic drag in Asia throughout the 2020s will also be acute. But regardless, the importance of the Asia-Pacific region in powering global growth will continue to rise.