Belt and Road: One masterplan, six economic power corridors

China’s Belt and Road set six economic corridors to focus investment, addressing diverse regional needs and ensuring the greatest national and regional impact.

Corridors of Power

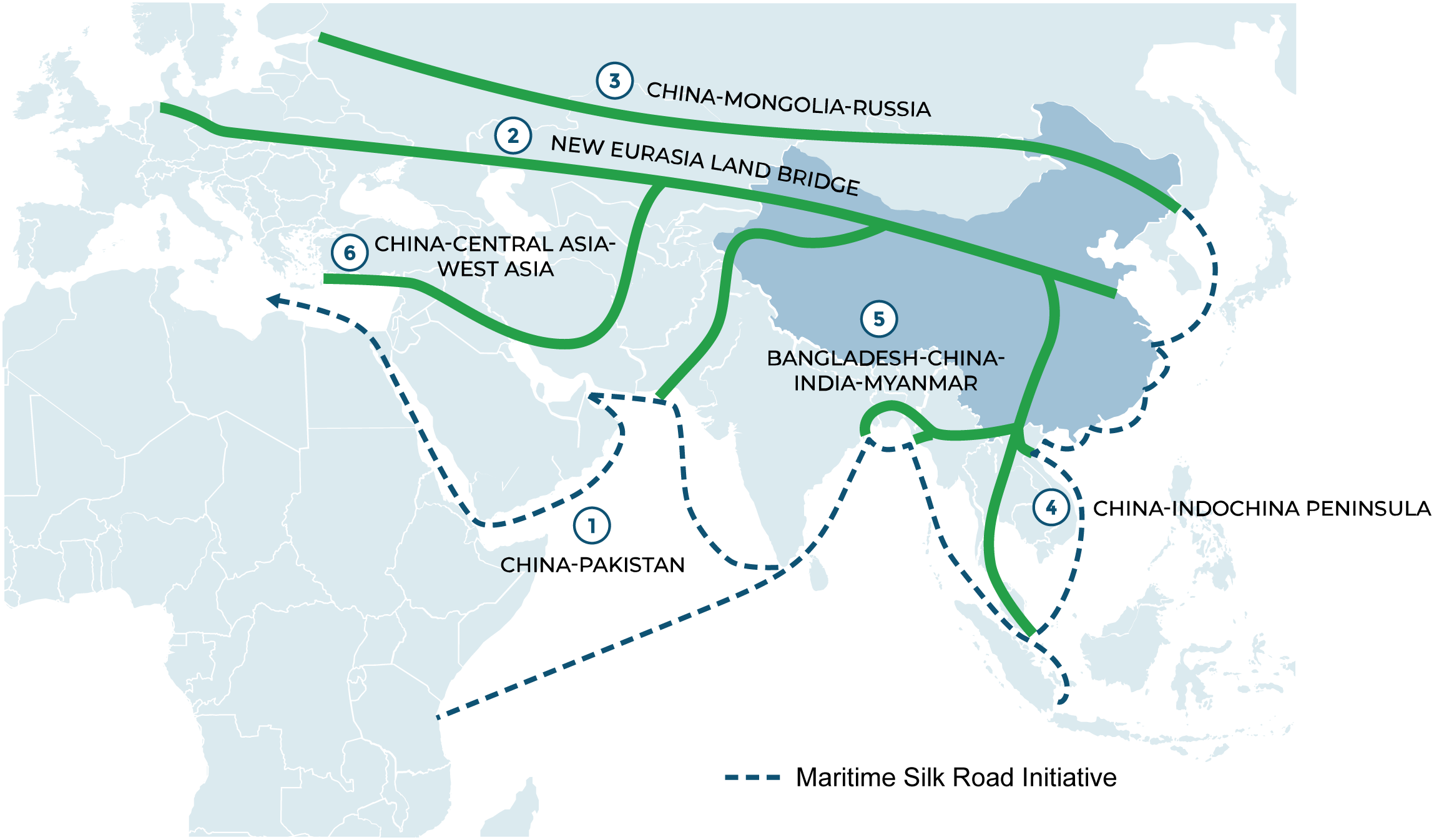

When China began the Belt and Road (BRI) initiative partnering with dozens of countries, six economic corridors were defined. Given that Belt and Road covers such a vast area, this made a lot of sense. With all the diverse challenges and needs across the different regions, the corridors helped to create areas of focus, and ensure investment would be channelled to where it will have the greatest impact on national and regional economies.

The six corridors are:

- China-Pakistan

- New Eurasia Land Bridge

- China-Mongolia-Russia

- China-Indochina Peninsula

- Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar

- China-Central Asia-West Asia

In 2017, The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) analysed each corridor and concluded that BRI investment would benefit each differently. According to their report:

- Incremental improvements in trade facilitation will lead to the biggest trade gains in China-Mongolia-Russia, followed by China-Pakistan, then the China-Indochina Peninsula corridor.

- Hard infrastructure investments will produce the biggest trade gains in China-Pakistan, then China-Indochina, then Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar.

- Improvements in information and communications technology will most benefit China-Mongolia-Russia and the New Eurasian Land Bridge.

Since these corridors were conceptualised, development along each of them has progressed at differing rates, and some are not deemed fully ‘active’ yet. But by looking at each in turn, we can see that though levels of progress and investment differ widely, they share the same fundamental goal of opening up economies and boosting trade.

China-Pakistan

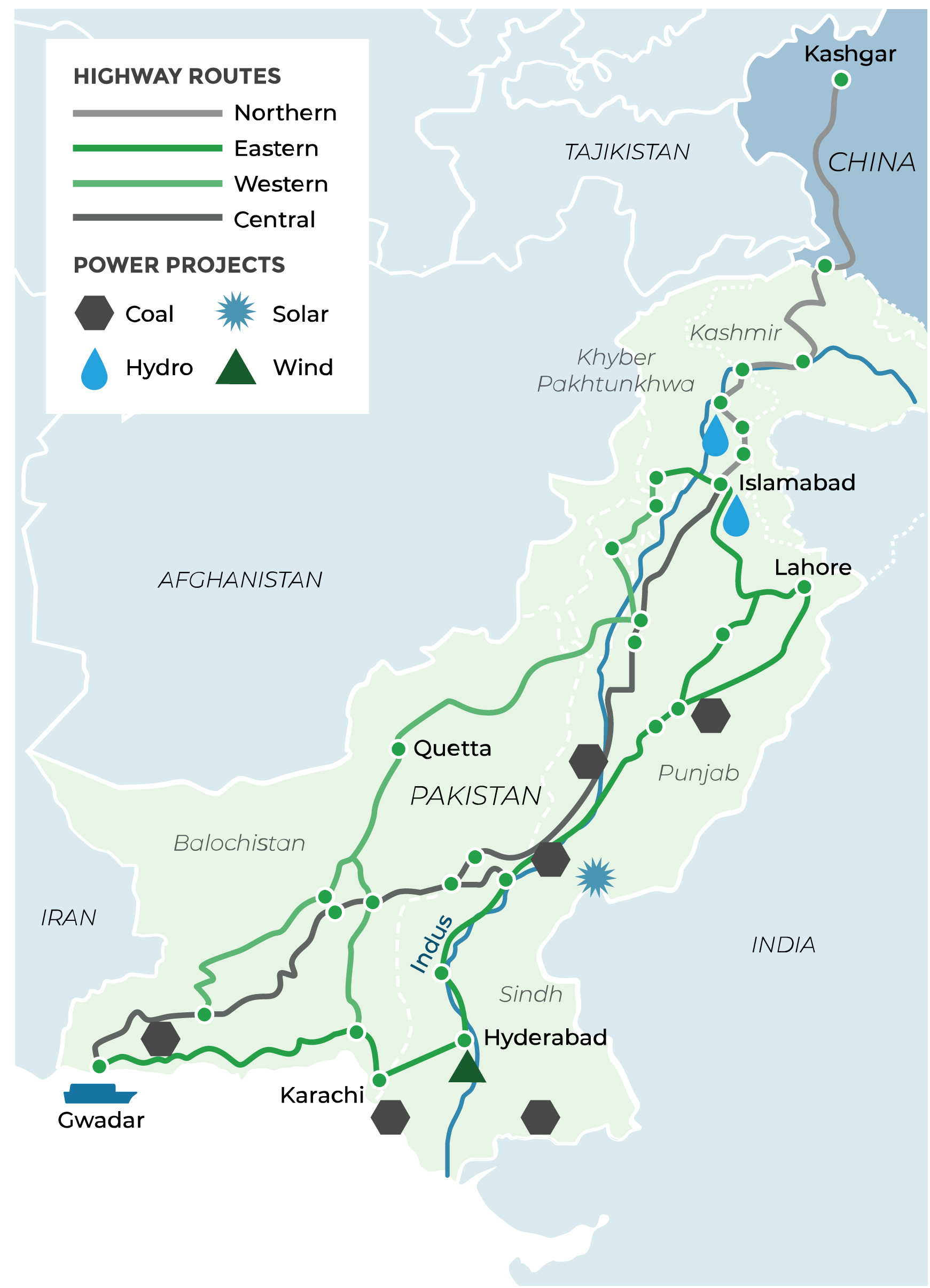

The corridor linking China and Pakistan has been described by Beijing as “the fastest and most effective” of the BRI projects. In both Beijing and Islamabad, the hope is that the investment in infrastructure will strengthen the economic and political bonds between the two countries.

With Pakistan’s underfunded infrastructure, it is plain to see why Islamabad would be attracted to Chinese investment on this scale. Up to USD62 billion is to be invested in this corridor; USD12.4 billion was already invested in power plants alone by the end of 2019. Once the fishing port of Gwadar has been transformed into the largest port in South Asia, China will gain direct land access to the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean, bypassing the Malacca Strait chokepoint, through which much of China’s crude oil imports currently pass.

With this corridor, it will also be easier for China to sell its goods to Pakistan’s growing middle class. However, the existence of this corridor has also created one of the most difficult geopolitical obstacles across the entire sweep of the BRI. India has expressed concerns that the corridor passes through disputed territory in Kashmir and, publicly at least, has withheld support from the BRI until its geopolitical concerns have been addressed.

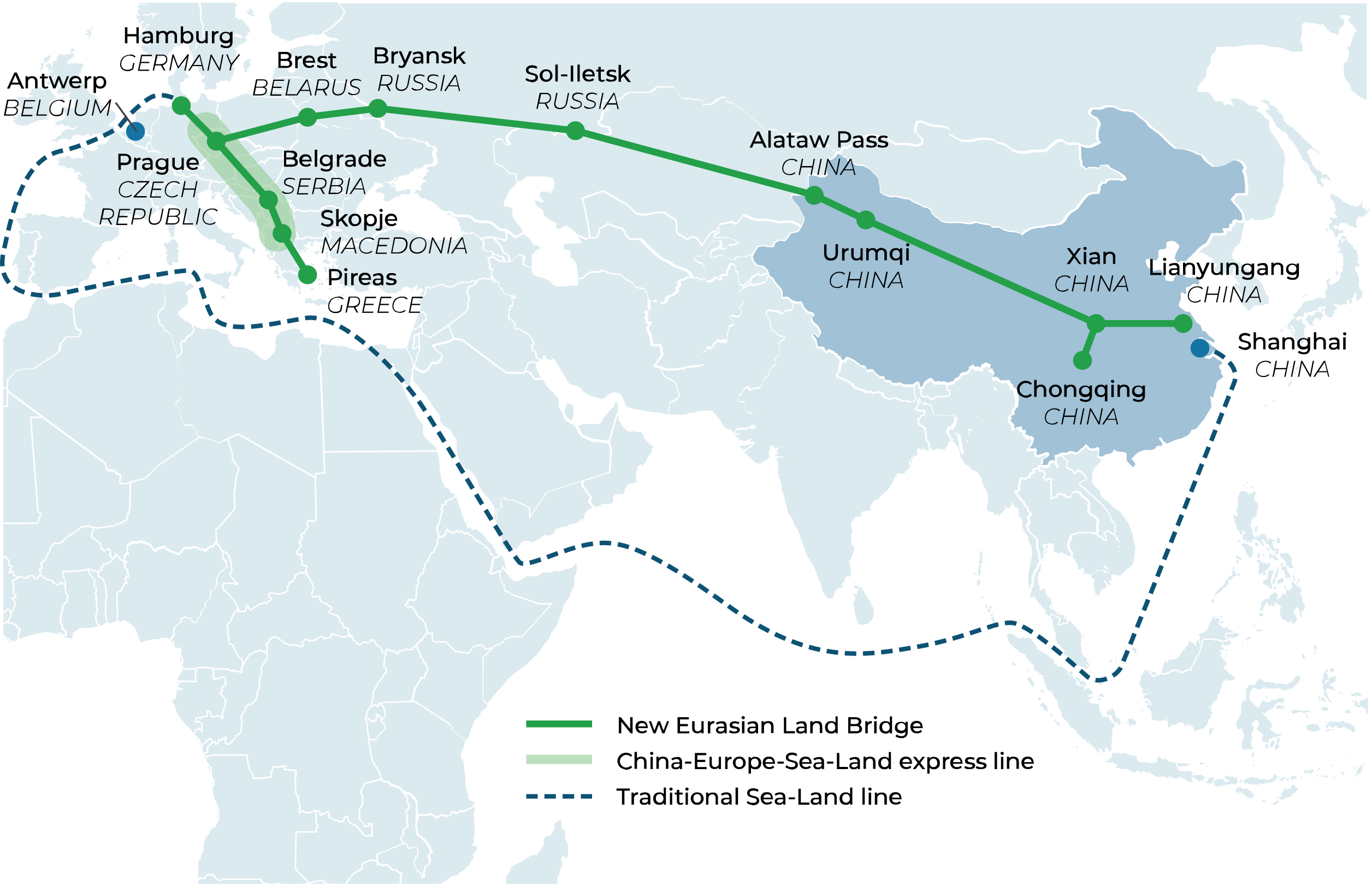

New Eurasian Land Bridge

At the heart of this corridor is an international railway line that connects China with Russia, Central Asia and Eastern Europe and then Western Europe. With the route passing through Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus and Poland, before linking up with the European railway network, it cuts the time and cost of transporting goods, and promises to help invigorate the economies of western China and Central Asia, not to mention important European dry ports like Duisburg in Germany.

China-Mongolia-Russia

Mongolia opened its first expressway in 2019. China Tiesiju Civil Engineering Group built the landmark project, tying Belt and Road to the country’s Steppe Road Program. The expressway links Mongolia’s new international airport to the Yarmang toll station and is expected to boost both passenger traffic and the local economy.

Elsewhere, efforts to reinvigorate Russia’s Eurasian Land Bridge are also expected to lead to considerable advances in trade along this corridor. One of the most high-profile projects is the construction of a railroad bridge over the Amur River that borders China and Russia, dramatically reducing the journey time between the countries. Construction is slated for completion by the end of 2020.

In relative terms, China’s trade relationships with Russia and Mongolia are not yet that large, although trade is growing rapidly between China and Russia (estimated at USD110.8 billion in 2019) and a free-trade deal between the two nations may see an explosion of commerce in the region. China is already the largest source of imports and exports for both Mongolia and Russia.

China-Indochina Peninsula

Boosting trade is just one of the benefits of the projects along this corridor, which links China with the five countries of Indochina – Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam – and also with Malaysia and Singapore. It’s hoped BRI investments will help improve the under-resourced infrastructure in the region and also tie in with smaller national projects like Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor and Malaysia’s Digital Free Trade Zone.

All the countries in this region, with a significant percentage of their exports heading to China, will benefit from improved connectivity.

To that end, China is building rail links through Laos and Thailand that will create a direct rail connection from Singapore to Kunming and beyond. A high-speed rail project between Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, though currently shelved, would slash travel times along that route even further.

Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar

So far, this is one of the least active corridors, largely because after several meetings of a joint study group on the project, India and China have been unable to reach agreements on several points. One of the most important projects along this route is the construction of oil and gas pipelines through Myanmar, which provides China with another alternative to shipping its oil through the Malacca Strait.

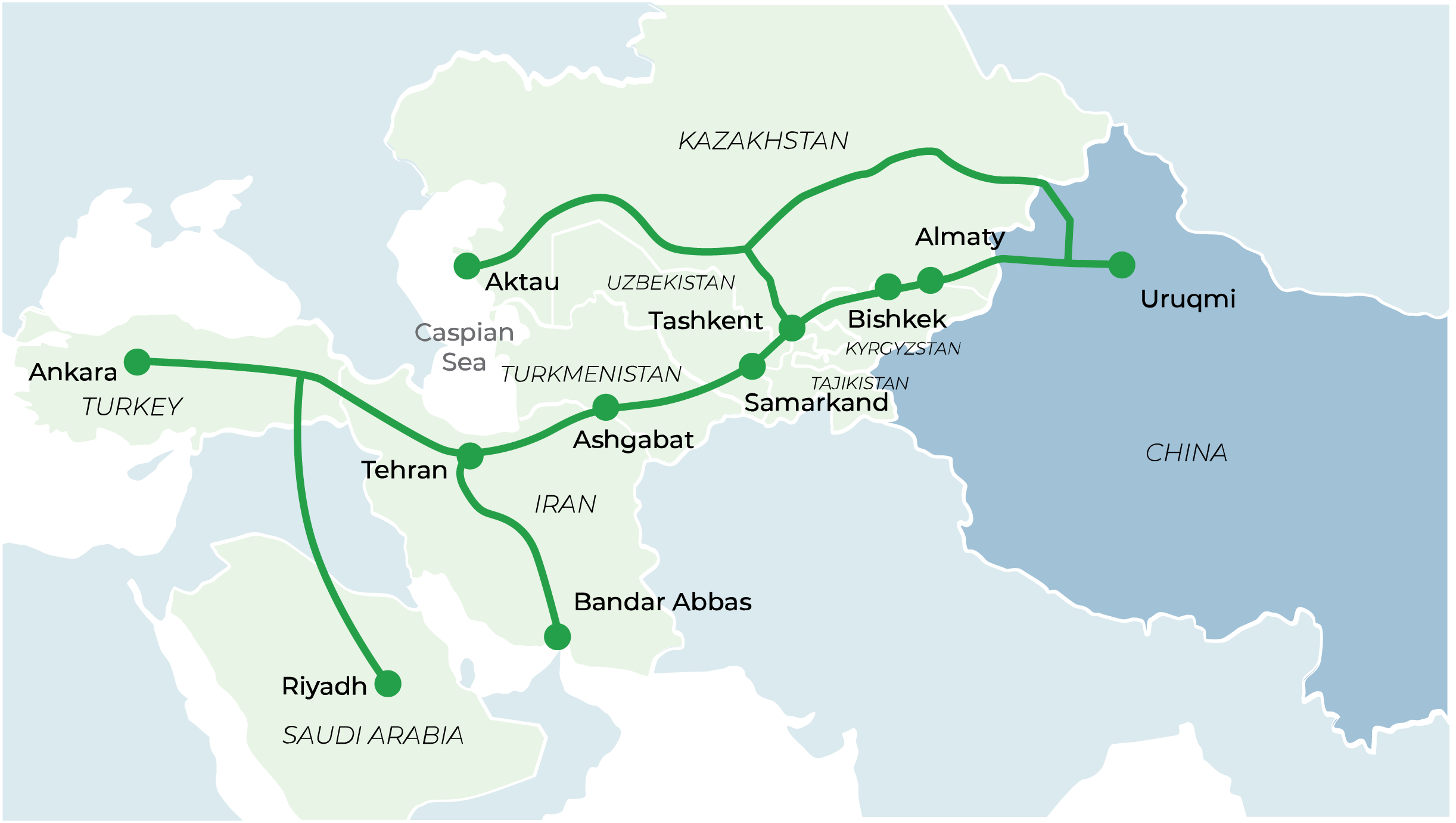

China-Central Asia-Western Asia

By linking railway networks from China to the Mediterranean Sea, this economic corridor enhances the connectivity between China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Turkey. In addition to investing in rail, China is also developing roads and other infrastructure projects that could transform the economies of Central Asia, which only have limited trade relations at present.

Each corridor presents different opportunities for trade and investment, whether it’s commodities moving through China-Mongolia-Russia, logistics along the Eurasian Land Bridge, infrastructure in Central Asia or Pakistan, or oil and gas through Southeast Asia. For Chinese and overseas companies looking to capitalise on the BRI, understanding the characteristics of each corridor will be critical to capturing those opportunities.

This article was also published on Bloomberg.com.

Explore more insights

MiCA a banks blueprint for digital assets success

Regulators craft crypto rules to protect consumers and ensure stability. As adoption grows in Europe, crypto cus…