Belt and Road: An initiative committing to global free trade

BRI is encouraging global free trade and international business cooperation by aligning the interests with development goals of participating countries.

Free Trade Finds a New Ally

In its World Economic Outlook report in July 2018, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said rising trade tensions prompted by protectionist policies posed a grave threat to the global economy.

“Avoiding protectionist measures and finding a cooperative solution that promotes continued growth in goods and services trade remain essential to preserve the global expansion,” the IMF wrote.

This is a clear rallying call to the forces of global free trade. But where once such an exhortation might have been directed at the more managed economies of the East, this one was clearly aimed elsewhere. While protectionism has been taking hold elsewhere, China has been energetically pursuing new deals, most of which mesh with the trade and development goals of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

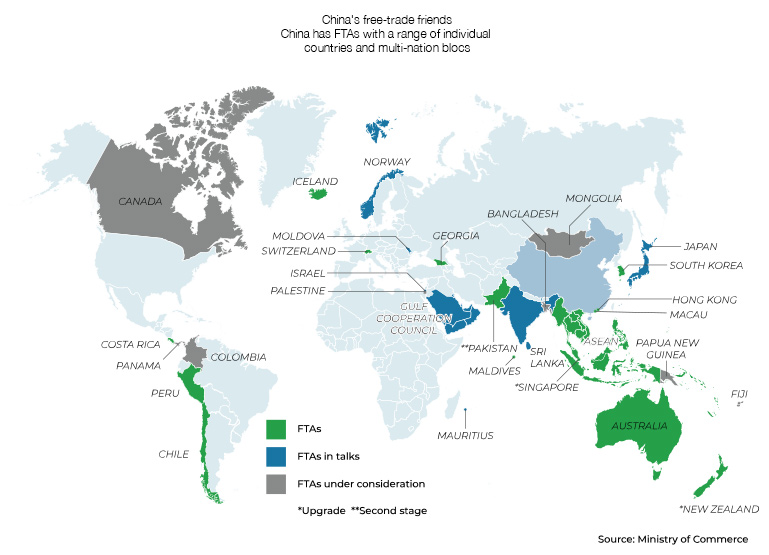

According to US Central Intelligence Agency figures, 73 countries count China as their largest partner for exports or imports (or both), compared with 45 countries counting the US as their largest partner. China has existing free-trade agreements (FTAs) with 21 countries, and according to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce another 13 new or upgraded agreements are under negotiation, and a further 10 under consideration.

New deals

After the US walked away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership free-trade agreement, China opened the door for alternatives that could potentially create just as many opportunities for business in the region.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, for example, is a proposed free-trade agreement that would link China with the 10 member states of The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, as well as five of the largest economies in Asia-Pacific (Japan, India, Australia, South Korea and New Zealand).

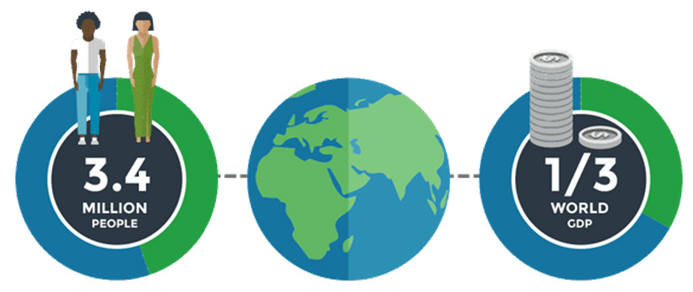

If signed on schedule in November 2018, the agreement would form a trading bloc that covers 3.4 billion people and about one-third of the world’s GDP.

China has been astute in encouraging trade and international business cooperation by aligning the interests of the BRI with national development goals of participating countries. In Kuwait, China has linked its BRI projects with the government’s ‘Kuwait 2035’ plan to transform the oil-dependent economy into a trade and financial hub. The Kazakhstan government has formally aligned its own ‘Bright Road’ development plan with the BRI.

On a larger scale, in May 2018 China signed a free-trade agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which covers Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. China and Russia are in talks to link the EAEU with the BRI. Sino-Russian trade is forecast to reach USD100 billion in 2018, and a formal trade deal could generate billions more.

Redrawing the Map

Step by step, and deal by deal, the BRI is redrawing the map of global trade, aiming to turn formerly peripheral markets into hubs and creating new opportunities for international companies.

By building infrastructure that cuts the costs of commerce, and forging agreements that reduce tariffs, the BRI could raise the value of global trade by 12 per cent through 2030, according to some estimates.

Depending on how quickly infrastructure projects reduce the costs of commerce, for some countries like Russia, Poland, Nepal, Myanmar and Kazakhstan, trade could grow by as much as 45 per cent.

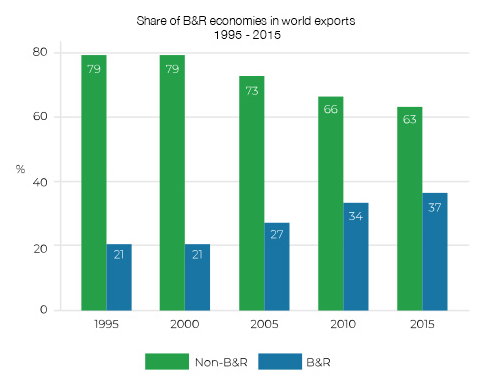

The momentum provided by BRI is enabling countries along the routes to steadily increase their share of global trade. In 2017, for the first time, China’s imports from BRI countries grew faster than its exports, demonstrating that for all the doubt surrounding China’s intentions, its stated commitment to global free trade amounts to much more than mere lip service.

This article was also published on Bloomberg.com.

Explore more insights

South-South Trade: A growth engine for emerging markets

South-South trade has grown considerably over the past decade and now accounts for one-fifth of global trade. Su…