2018 expectations: beware of the dog

2018 is likely to be another good year for global growth, with the world economy expected to expand by 3.9 per cent, up from 3.7 per cent in 2017.

The US and euro area are enjoying robust business and consumer confidence, and both are likely to exceed 2 per cent growth in 2018, similar to in 2017. Asia excluding Japan should once again be the fastest growing region in the world at 6.1 per cent. We expect growth to be up from 2017 levels in the Middle East and North Africa region (rising to 2.9 per cent), while Africa and Latin America should continue to recover from 2016 lows, expanding by 3.4 per cent and 2.4 per cent, respectively.

This is no time for complacency. Growth is still below the 4.2 per cent average seen in the 10 years before the global financial crisis

While this is encouraging, this is no time for complacency, especially as growth is still below the 4.2 per cent average seen in the 10 years before the global financial crisis.

Emerging markets face looming risks, and these are not merely geopolitical. In the Year of the Dog, ‘barks’ could easily become ‘bites’.

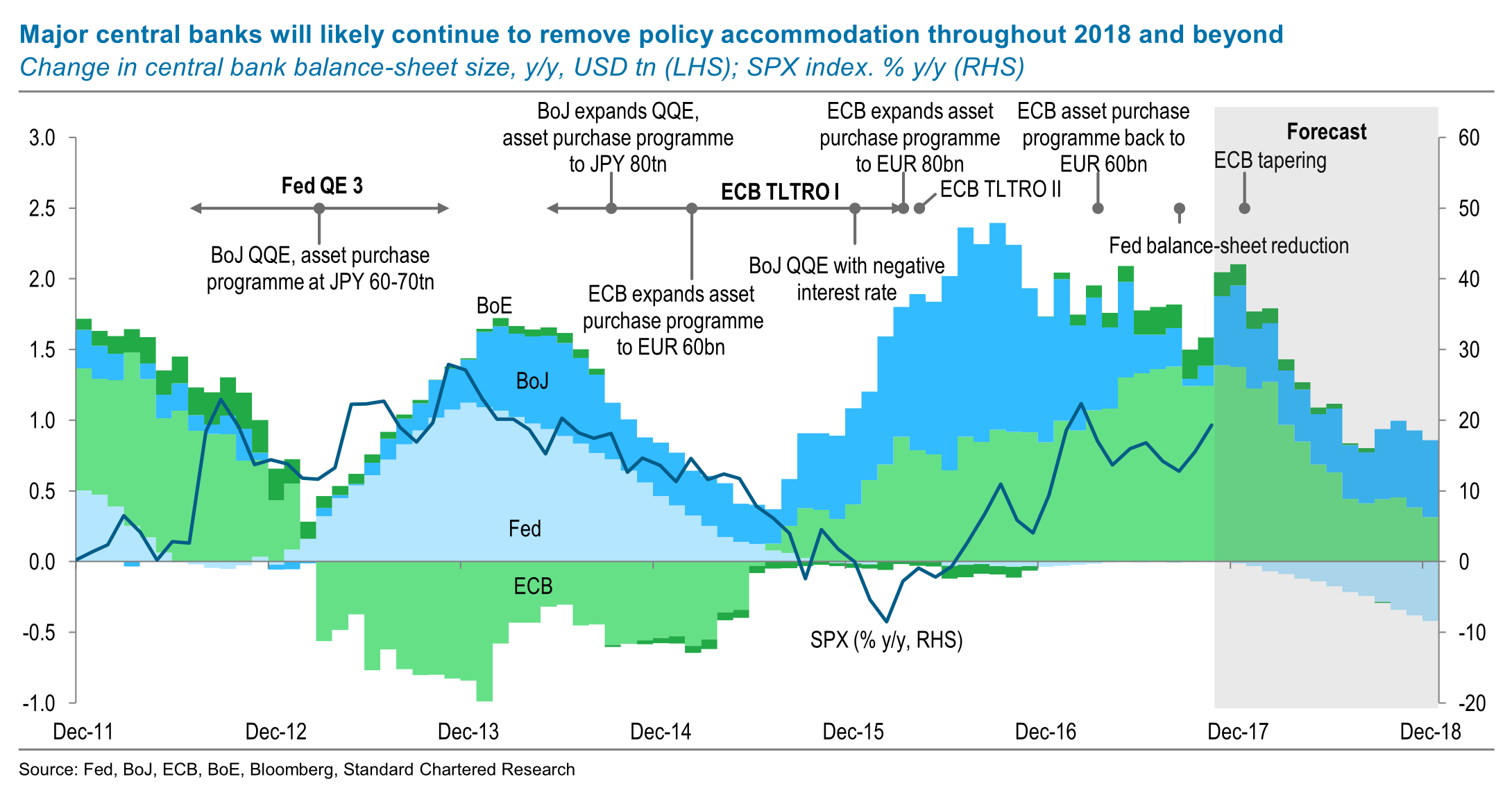

We expect the Federal Reserve (Fed) to hike its interest rate twice in the first half of 2018, taking it to 2 per cent by the end of June. We see a risk of a third hike in the second half of 2018. If the Fed were to be even more aggressive than we expect, this could reduce flows into emerging markets. But perhaps even more important than the Fed in 2018 are the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan.

In the past two years, central banks of the major, advanced economies have continued to expand their balance sheets significantly – even after the Fed ended its quantitative easing programme in 2014. But now the most aggressive monetary easing experiment in living memory is about to end. This should start to affect markets and the global economy by the second half of 2018, when aggregate balance-sheet expansion is due to slow to a quarter of its current annual run rate.

We think central bank balance sheets will begin to shrink outright in 2019, making it harder for markets to shrug off bad news. In this case, if the bark turns into a bite, it could be painful.

Major central bank support for growth and the markets will likely fade fast, starting from the second half of 2018

Global trade could deliver a second potential bite. In 2017, strong Asian exports were buoyed by two temporary factors: recovering export prices and China’s inventory restocking cycle. Both are likely to fade this year. The good news is that electronics producers, mainly in North East Asia, should continue to benefit from the structural rise of the internet of things.

In China, growth is likely to continue to soften in 2018 but remain on track to achieve the target of doubling 2010 real GDP by 2020. But risks from prior leverage growth excesses continue. Growth and productivity have suffered for years under the weight of excessively leveraged state-owned companies. We expect little change on this in 2018, while innovative and less leveraged sectors should grow strongly. Deleveraging efforts underway should help to reduce risks in the longer term, although the complex nature of the financial system remains a challenge. China’s economy will likely be a tale of old, slow growth, excessively leveraged sectors versus the faster growing new services industries, which are boosting consumer spending.

While China’s households are experiencing rapid credit growth, this is from a low base and is unlikely to pose a risk for the next three to five years. In fact, China’s household spending may increasingly benefit other emerging markets, not just via tourism but also as China rivals the US as a services and consumer-led economy in the coming years.

We expect a significant increase in China’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation, to 2.7 per cent in 2018 from 1.6 per cent in 2017. Our forecast, among the highest in the market, where the consensus view is 2.2 per cent, is based on several factors. The softness of the CPI in 2017 was mainly driven by food deflation, which is rare in China’s history. Recent data suggests that food price increases have normalised. Also, there are early signs that higher producer prices are being passed on to consumers.

Finally, the services sector has become a stubborn source of inflation, surpassing 3 per cent in recent months. The need to contain inflation could mean that policymakers are more tolerant of tighter financial conditions, including keeping the renminbi steady to slightly stronger on average against a basket of major currencies in 2018.

As funding costs rise, it will be harder for investors to ignore bad news

In the Year of the Dog, with consensus predictions so focused on the strength of the global economy, we stress the need to remain wary of risks, and not just the geopolitical ones. Major central bank support for growth and the markets will likely fade fast, starting from the second half of 2018. Asia’s export strength in 2017 will likely ease. As funding costs rise, it will probably be harder for investors to ignore bad news.

Important disclosures regarding content from Standard Chartered Global Research can be found in the Global Research Terms and Conditions.