Funding the clean energy transition: A look at blended finance

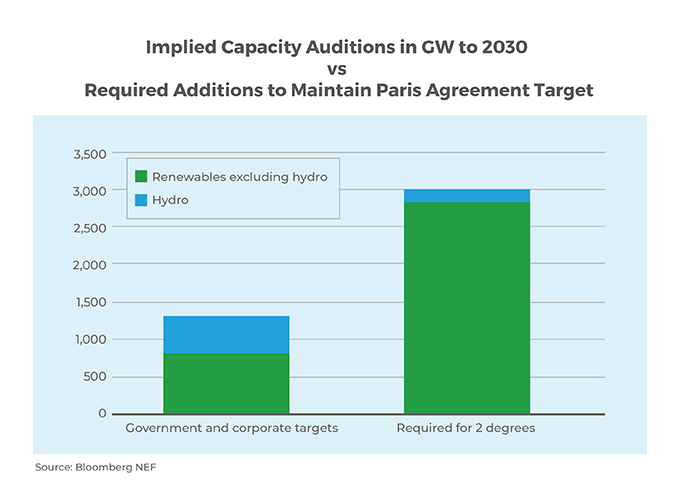

Governments and private companies around the world are currently committed to around USD1 trillion worth of new renewable energy capacity through 2030, just a third of what is required to keep the rise in global temperatures below 2 degrees1. Maintaining the Paris Agreement target requires large investments in emerging markets, which will account for the lion’s share of demand growth and power sector emissions going forward.

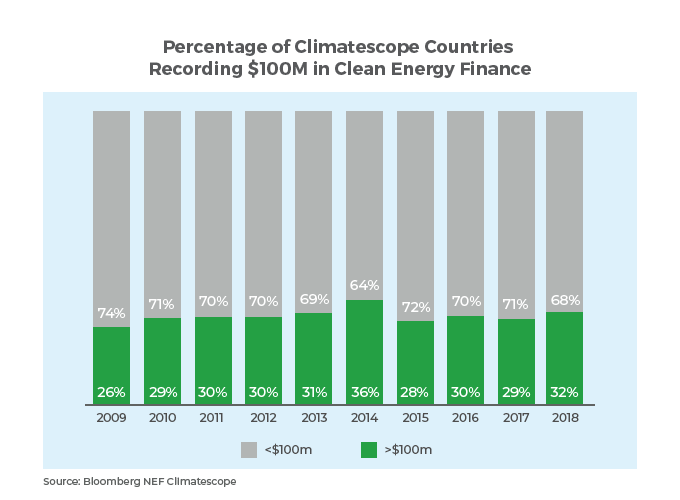

While the number of countries investing in clean energy is rising, capital volumes remain far below what is needed to accelerate the clean energy transition. Of the 104 emerging markets surveyed in the 2019 BNEF Climatescope report, on average, less than one-third recorded more than USD100 million in clean energy investment in nearly every year over the decade through 2018—roughly the amount required to fund one major solar or wind project.2

“According to our Opportunity 2030 report, the total private-sector investment needed to generate and transmit electricity in all emerging markets by 2030 is around USD4.2 trillion,” says Daniel Hanna, Global Head of Sustainable Finance at Standard Chartered. “While the private sector can play a role through green bonds and ESG funds, that’s largely a developed market story. We need to find new ways of funding that bring the government and private sector together.”3

Part of the solution may lie in blended finance—a structuring approach that enables public and private investors with different objectives to invest alongside one another. Blended finance addresses perceived and real risk as well as poor risk/reward ratios—the main barriers for private investors—through concessional capital and guarantees for development.

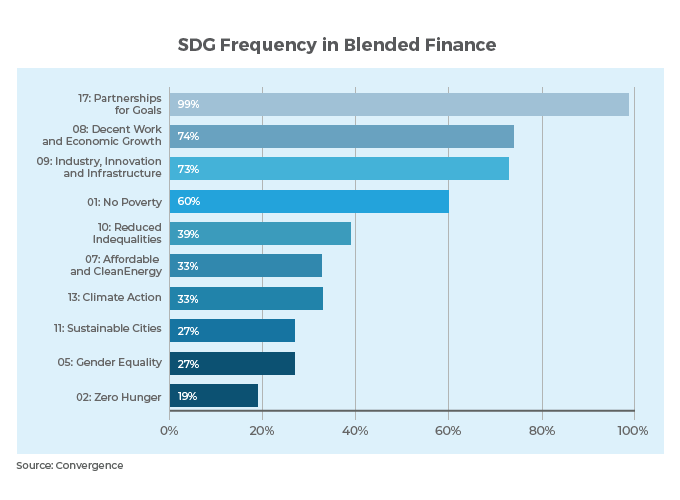

Around a third of blended finance deals target UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7: Affordable and Clean Energy. Indeed, a 2018 Climate Policy Initiative report shows that, together, the 46 emerging markets that met the criteria for clean energy set by its Blended Finance Taskforce represent an investment opportunity of more than USD1 trillion.4

“Blended finance can prove useful for renewables in places with high country and project risk,” says Joan Larrea, CEO of Convergence, the global network for blended finance. “It can occur on the project level or within a larger financial structure (such as a fund) that aggregates multiple smaller projects, which delivers the combined magic of the portfolio effect and blending of different kinds of capital.”

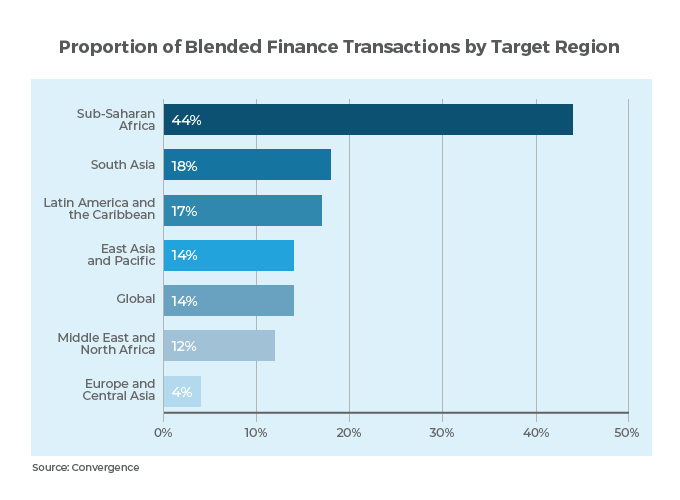

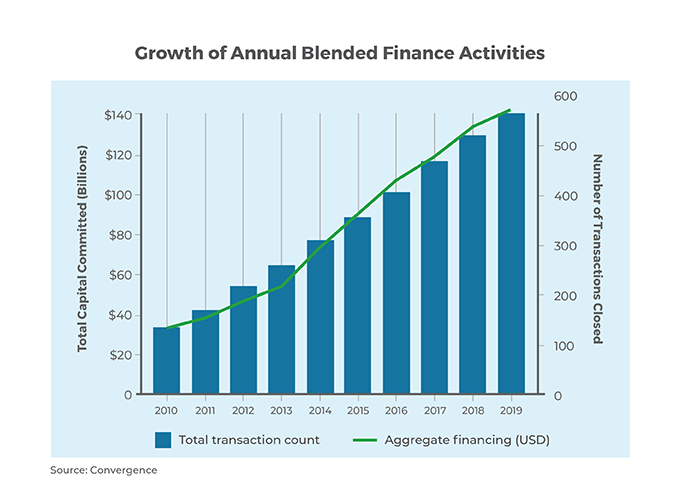

In the past few years, Convergence has tracked around USD47 billion worth of activity in emerging markets renewables across some 127 deals—the bulk of them in Africa. Infrastructure players are the most common private-sector participants in single-project transactions. Where fund structures are involved, institutional partners and foundations often step forward.

“We’ve done USD5 billion worth of blended finance over the last four years,” Daniel says. “There are some interesting models around blended finance and clean tech such as the World Bank’s Scaling Solar program. More initiatives like this could help tackle the funding challenge.”

Standard Chartered participated in one such deal in January 2020. Working alongside the Asian Development Bank (ADB), it is providing long-term financing to develop and operate a 50-megawatt photovoltaic solar power plant in Tay Ninh Province in Viet Nam. The ADB’s participation will help to ensure bankability and, in turn, catalyze commercial financing for one Vietnam’s first large-scale solar power project finance transactions.5

The blended finance market is a fraction of what it could be. While it has grown rapidly, only 26% of transactions target low-income countries.6 In less developed countries, two common challenges prevent blended finance for clean energy from reaching its potential: information asymmetry and inadequate project pipelines.

Blended finance is not simply a matter of creating a structured financial instrument by mixing public and private resources. A broad range of actors including investors, financial intermediaries and project developers must collaborate on governance, fundraising, identifying investment-worthy projects and more. Information asymmetry, transparency and mismatched objectives often create coordination challenges.7

“Blended finance is a tool for situations where the risk and the opportunities are mismatched,” Joan says. “The longer term solution to increasing the flow of finance cannot rest on blended finance alone. It will have to involve governments doing regulatory work to remove risk and barriers that prevent local capital from entering into transactions.”

Securing a pipeline of quality projects is another common challenge. To scale, blended finance requires a strategy to develop the underlying pipeline from the origination phase.8 Nearly two-thirds of investors who have participated in blended finance have only been party to one transaction9 due to an inadequate pipeline of sizable, high-quality projects.

“There probably aren’t enough blended finance transactions that are crafted in a way that allow them to be a habitual part of an investor’s repertoire,” Joan says. “Convergence has been deeply engaged with donors to raise awareness of the scale and risk profile that are important to attract institutional investors.”

Blended finance is not a silver bullet. The total private-sector investment opportunity across SDG 6: Clean Water & Sanitation, SDG 7: Affordable & Clean Energy, and SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure stands at USD9.7 trillion, according to Standard Chartered’s Opportunity 2030 report. Only innovative new solutions can help fill the gap.

“We need to innovate scalable solutions that mobilize not tens of millions but trillions of dollars,” Daniel says. “Sometimes the focus is too much around very small bespoke solutions that don’t match the scale of the problem.”

Funds that pool public and private resources around a specific issue or theme are helping. Thus far, these results-focused funds have largely been used for health- and climate-related public goods. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, for instance, has several dedicated climate funds. Despite their success in mobilising resources, these funds fragment aid architecture, sometimes making it difficult for less developed countries to access funding.10

A more recent innovation comes from Standard Chartered, which launched the first U.S. sustainable use-of-proceeds syndicated subscription finance facility for the KKR Global Impact Fund. All investments funded under the facility must meet stringent criteria to ensure alignment with the SDGs and are subject to ongoing monitoring and reporting of their impact on specific SDGs after the investments have been made.11

“On the private sector side, I think we need to be clearer around the impact point,” Daniel says. “Being transparent around what the impact is and trying to show how you are capitalising and addressing the challenge is important to make investors comfortable to participate.”

Produced by Bloomberg Media Studios in partnership with Standard Chartered.

With topics around urban transformation, energy transition, the future of transport and critical infrastructure across Asia, Africa and the Middle East, the campaign will unearth fresh trends and showcase how we are supporting clients towards a more sustainable and inclusive future.