One way road?

It is popular in some quarters to portray the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as purely an exercise in Chinese self-interest, a loaded game offering few opportunities for outsiders. In mid-2017, a former chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in China summed up that point of view to the New York Times, saying the initiative would be a “non-starter” if it was all about bringing Chinese goods to Europe.

Belt and Road is undoubtedly Sino-centric in design and management; every nation, after all, acts in its own interest. However, the sheer scale of the initiative also implies it will be impossible for Chinese firms to fulfil the entire BRI vision alone.

The massive centrally-planned infrastructure projects being built by Chinese companies generate most of the headlines. The locally-planned bolt-on projects, and the opportunities for new business that are created as infrastructure begins to generate trade, receive less attention. Factor in the many Chinese and local firms that will require overseas partners as Belt and Road evolves, and the potential for international participation in the initiative to blossom is evident.

As Joe Kaeser, CEO of the German industrials conglomerate Siemens, told an investment seminar in New York in early 2018, BRI will offer approximately EUR100 billion (USD124 billion) worth of infrastructure collaboration opportunities with Chinese engineering, procurement and construction companies over the next seven years.

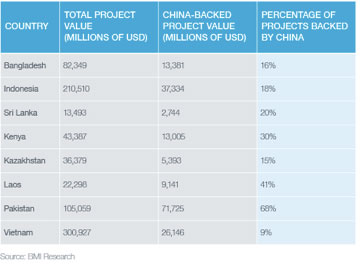

Figure 1: BRI projects in selected countries and the proportion backed by China to date

As Figure 1 shows, there are plenty of gaps in the funding schedule. Countries hosting the infrastructure will hope their domestic companies can make up much of the shortfall, but many of these may need to seek partnerships with international investors.

These global partnerships will likely be necessary for a variety of reasons. Firstly, Chinese companies have run into problems in some countries, finding that they can lack specialised skills which they have not previously required when doing business in China. Such skills include managing labour and political relations, plus social and environmental concerns. In China, resettlement, compensation, environmental offsets and social monitoring services are usually left to government departments, so within private companies, experience in these matters is often limited. In such areas, experience in international and mature markets gives European and US companies a competitive advantage that BRI contractors will often be keen to utilise.

Secondly, with so much large-infrastructure construction ongoing, it is probable that Chinese policy banks will become stretched as major projects from the early years of BRI approach completion. This will likely mean Chinese companies will be searching for international partners that can contribute capital to projects.

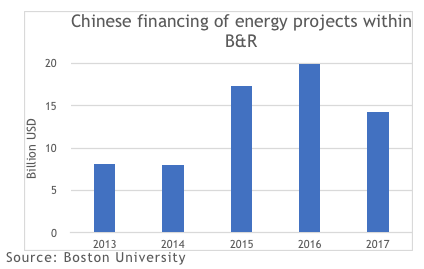

There is already evidence that funding is slowing down as Beijing looks to rein in capital outflows. According to a Boston University study, energy financing from China in BRI countries dropped from around USD31 billion in 2016 to USD3.2 billion in 2019.

This does not mean that Belt and Road is failing; progress on vast projects in multiple countries is testament to the change the initiative is bringing. However, as financing from China becomes harder to secure, a growing number of Chinese and host-country contractors and investors will no doubt look for assistance in selecting, structuring and managing projects in a way that mitigates risks and attracts foreign capital.

International companies can also provide crucial expertise in project due diligence and structuring, contract negotiation, and in labour, tax and insurance regulations. There are also opportunities to supply products and technology needed for BRI contracts. US firms already benefitting from this demand include Honeywell and General Electric, through its partnership with Sinomach in Africa.

To improve the quality of their BRI tenders, Chinese companies look to engineer partnerships with western companies in a variety of ways, through contract sharing, service procurement, and at times, acquisition. There are already multiple examples of mutually-beneficial partnerships being generated by Belt and Road in which Chinese enterprises have sought the technological or reputational advantages of international companies:

In many cases, the best opportunities for international companies along the Belt and Road may lie not in infrastructure projects themselves, but in the immediate growth that accompanies them, which is perhaps why they receive less attention.

For example, Chinese power plant investments in BRI countries such as Cambodia, Laos, Pakistan and Tajikistan have created opportunities in electricity grid expansion and management. Greater generating capacity is irrelevant without the ability to transmit electricity to the right locations at the right times, and solutions require not only investment in power lines and substations but also in sophisticated network management systems, in which US and western European nations are market leaders.

Growing trade and traffic, particularly from Europe and the transport hubs at Greece’s Piraeus Port and Germany’s Duisburg Dry Port, will provide avenues where international investment and know-how can be expected to bear fruit. The belt connecting China and Europe is emerging as a major logistics corridor that generates opportunities, while the New Eurasian Land Bridge should open up the western regions of China that are currently difficult for international companies to access.

Many projects associated with Belt and Road carry the risks of doing business in emerging markets. Some countries along the corridors have underdeveloped or underenforced regulatory frameworks. Others also carry geopolitical risks and see occasional security threats. Prudent investors will therefore insist on robust risk-management measures before entering these jurisdictions. Providing this, again, is an area in which many Chinese companies have limited experience.

As private-sector involvement in Belt and Road grows, companies seizing the available opportunities will need to know how to deal with issues such as non-tariff trade costs, competition policy and intellectual property protection. There are already a number of international companies with considerable expertise in these territories.

Just as the Belt and Road’s long-term goals depend on financial integration, China recognises that it also depends on business cooperation. While the initiative will remain China-led, the importance of international partnerships to its success will only get stronger.

This article was also published on Bloomberg.com