Mindset shift: why embracing collaboration with China could be the key to securing the future of the metals and mining sector

on September 23, 2024Richard Horrocks-Taylor, Global Head Metals & Mining, Standard Chartered, examines the state of play in China and its role in securing the metals to meet the needs of the sustainable transition.

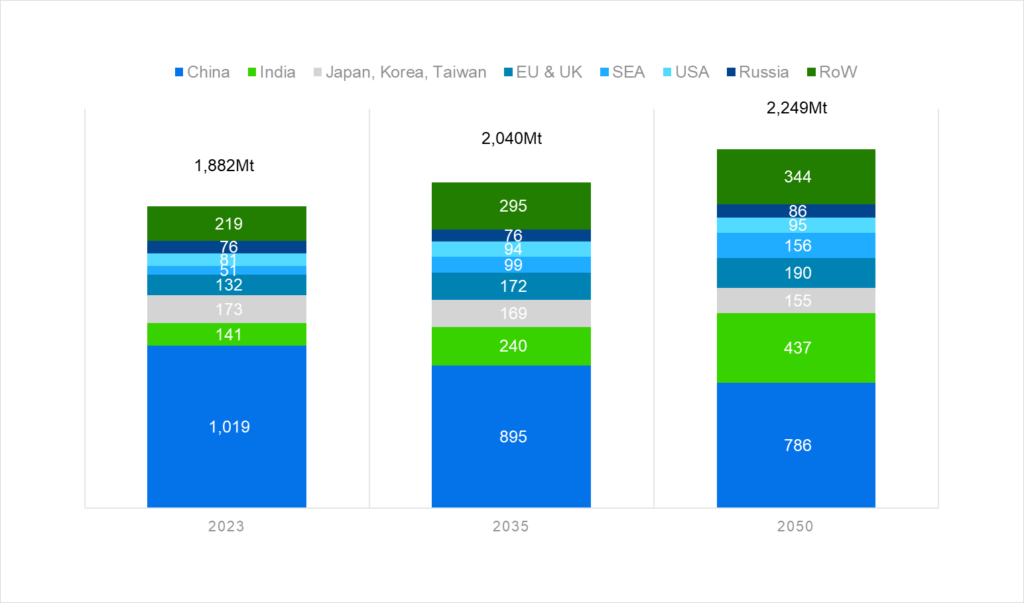

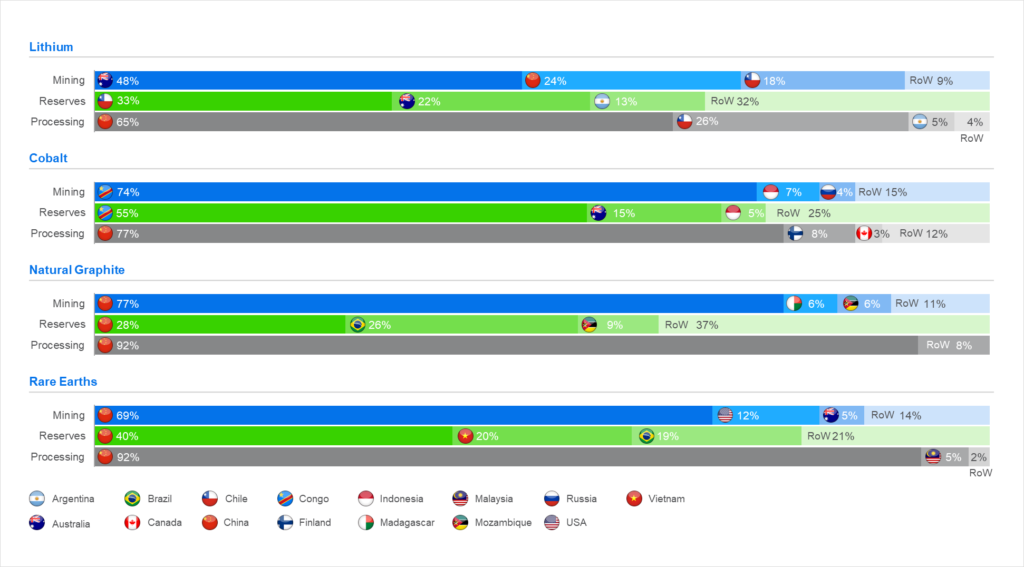

China is a behemoth in metals and mining, both as the biggest consumer of minerals on the planet and the largest producer of the world’s most sought-after metals. It dominates the steel industry, producing 1 billion tonnes per annum (compared to the US, Europe and India, currently at only 120-140 million tonnes each), and it controls most of the world’s processing of lithium, nickel, graphite, cobalt and manganese. But a number of factors mean that its stronghold in the sector is facing uncertainty.

China’s steel market has peaked, with demand starting to fall initially from 1 billion tonnes to 900 million tonnes annually, driven largely driven by a slowdown in its domestic property market. This property related demand is expected to decrease further to around 100-150 million tonnes over the long term, from the current 250 millon tonnes projected for 2024. Seaborne iron ore prices have also fallen well below USD100 for the first time since 2022, highlighting the sector’s vulnerability. The recent, stark words of Baosteel’s chairperson, who described conditions in China as like a “harsh winter” that would be “longer, colder and more difficult to endure than we expected”, depict an outlook of significant strain and uncertainty for China’s steel market.

There are also weaknesses away from steel, with the price of base metals and battery materials, such as nickel, copper and lithium, being negatively impacted by the combination of oversupply and waning demand from Western markets’ battery material supply chains – largely as a result of a hiatus with respect to electric vehicle (EV) adoption. Indeed, following the initial stream of early adopters, demand from the US and Europe has been lower than expected.

Despite these challenges, China remains a dominant player in metals and mining – whether with respect to iron and steel or battery materials. Indeed, this will remain the case even if its steel production reduces materially in the next 10-15 years (see Figure 1).

Contenders will, of course, see substantial growth in the market (India’s steel production is set to more than double to 300 million tonnes by roughly 2040, for instance). But with approximately 90% of the metal-based items used globally being currently made in China, the country is ingrained at the very epicentre of the metals industry and, for the foreseeable future, will continue to be an invaluable source for domestic and international markets.

China: the supplier of choice for new metals demand

China’s vast experience and knowledge of the industry and its evolving markets have allowed it to build resilience and adaptability in this often unpredictable sector. It has, for example, unlike many commodity producers, become fully integrated across the entire supply chain, from mining and smelting to finished products. China also holds a dominant position in future facing commodities that are essential for the global energy transition.

As such, it is now actively at the forefront of developing the technologies and products that drive today’s demand for metals and minerals. In the EV sector specifically, it is leading by example, with approximately half of the vehicles on the roads of Beijing and Shanghai being electric. China is also a key player in renewable energies development, including solar panels (leveraging silica and aluminium), wind turbines (steel, aluminium and rare earths, etc.), as well as nuclear power (uranium).

Another fundamental part of China’s futureproofing strategy has been its remarkable investment into Indonesia’s nickel industry over the last decade. By deploying capital and its project delivery expertise, China helped Indonesia’s nickel production soar from 26% of the world’s output in 2018 to over 50% in 2023. This transformation has been driven by China’s ability to produce nickel through previously very challenging high-pressure acid leach (HPAL) technology, enabling cost-competitive production of battery-grade nickel to meet global demand.

Addressing the demand-supply conundrum

With its ingenuity, forward-looking strategies and unique skillsets around the development of new mines, China will be crucial as the industry seeks to address a pressing challenge in the mining sector: building enough projects quickly enough to satisfy demand. The International Energy Forum (IEF) estimates that to electrify the global electrical fleet of vehicles by 2050, at least 35 new copper mines will be needed to meet the demand2 of this essential metal for the green transition. Considering it can take up to two decades to build just one mine in the heavily regulated environments such as the USA, the picture this paints is far from optimistic.

Currently, much uncertainty surrounds how this is going to be achieved, but China’s engineering prowess could be a part of the solution. Its ability to innovate and deliver projects on time and within budget has made collaboration with Chinese groups attractive to many international players, particularly during the construction phase of new mines.

This has been seen first-hand through the Simandou Project in Guinea, for instance, where Rio Tinto recently formed a new joint venture with several key Chinese groups, including Baosteel, Chinalco and Winning, on what is the biggest iron ore project in the world. The collaboration has meant the project has had the combined benefits of excellent engineering, delivery speed and low costs from the Chinese, along with strong ESG oversight and advisory capabilities from Rio Tinto. This fusion of know-how has been the catalyst for the project’s successful delivery. Indeed, it had been in the works for 35 years, but has been able to be built in the last three to four years and is expected to be producing iron ore by late 2025-early 2026. It is partnership approaches such as this that can make what seems insurmountable, surmountable; the impossible, possible.

Realising the future mining landscape that is required cannot be accomplished without a joint effort; a cross-continental community that brings together the strengths and specialisms of multiple parties; both China and countries elsewhere.

China the acquirer

The geopolitical strains between China and the West endure, a barrier that needs to be navigated if we are to conquer the anticipated supply-demand issue. The impacts of geopolitical dynamics extend to China’s role within metals and mining M&A. Western pressure to restrict Chinese investment – which tends to be asset based rather than corporate takeovers of more diversified groups – has altered investment patterns, with some Western governments seeking to prevent Chinese acquisition of assets in key commodities, particularly those linked to the energy transition, on the basis of protecting national strategic interests. Canada, for instance, has blocked Chinese buyers from acquiring companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, a key listing venue for junior mining companies. This was recently seen in Zijin’s bid for Solaris Resources, for instance. Meanwhile, the US has reportedly pressured foreign governments to intervene in M&A processes to prevent Chinese acquisitions in the mining sector.

Many geographies, however, welcome Chinese investment and the technological and production capabilities it brings, particularly in renewable energy and the battery materials supply chain. Saudi and GCC countries are notable partners in this respect, with recent examples including the Baosteel JV with Saudi Aramco, and the Shandong Innovation with PIF in electrolytic aluminium. Elsewhere, Africa remains an important investment destination for China, despite some influence from the US to curb Chinese involvement. South America also remains a key destination, where significant investments in lithium in Argentina have been made.

Irrespective of geopolitical dynamics, because of China’s importance in the market, what happens in China is a key bellwether for the sector, and China’s current economic weakness is casting somewhat of a shadow on the global M&A sector. If, for instance, China’s property market further weakens and iron ore prices fall, large cap M&A deals may be put on hold.

While some consolidation within the sector is expected, China’s influence on the metals and mining landscape is unquestionable. Indeed, in public transactions that result in consolidation in key commodities such as copper, regulatory approval from China is often required, which typically stipulates divestment of certain assets. As active purchasers of assets, this in turn creates an avenue of opportunity for Chinese buyers, as was seen when Glencore acquired Xstrata in 2013, and ultimately divested the Las Bambas copper mine to Chinese SOE, Minmetals. One asset class of particular interest to China is gold. As China increasingly seeks to move away from its reliance on the US dollar, over time, it is strategically building up a large amount of gold as a reserve support for the renminbi.

The winning formula

As an industry, we are facing the monumental challenge of both transitioning away from fossil fuels and meeting growing global metal demand for future facing commodities. And ultimately, achieving this requires greater dialogue and partnership between China and the Rest of the World.

The success that such collaborations can bring has already been evidenced by the Simandou Project, and it is a united approach that will position us to deliver the commodities that will help us transition – a win-win for all. With its leading position in Asia, the Middle East and Africa, Standard Chartered is uniquely positioned at the juncture between China and the rest of the world to help connect buyers and create value for all stakeholders.

To move forward, a balance between embracing what China does well and protecting sovereignty needs to be achieved. As such, in many respects, the industry’s future success is dependent on a mindset shift, gradually transitioning perspectives and potentially misconceptions, and accepting the potential for China to bring real value to the table. By breaking existing barriers, opening a channel for dialogue and being receptive to the possibility of collaboration, the stage can be set for the new mining era.

1Sourced from publicly available data from the USGS and IEA, available here:

https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2024/mcs2024.pdf

https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/critical-minerals-data-explorer

2 https://www.mining.com/copper-humanitys-first-and-most-important-future-metal/